Ethno-Archaeology and Visual Anthropological Linguistics:

Parallel to the archaeological work, research Esther Morgenthal and her research assistant, Christophe Loua Bérété, were busy in the villages of Kansamana and Madina documenting the local traditions of ceramics production and collective knowledge of potter families in the area. This is how she experienced her research on cultrual practices and cultrual conceptualization of ceramics in Maninkakan speaking communities of Southern Mali:

On our arrival in Bamako, I saw the first pottery artefacts at the market stalls along the road while driving to the guesthouse. During the next days I had the opportunity to look for pottery produced for urban customers and offered for sale in the markets.

I asked myself: what kind of pottery is sold here, where does it come from and who are the sellers? Evidently, this is too modern and mass-produced to be part of any linguistic anthropological research – or am I mistaken? In retrospect, this visit to the market turned out to be important to classify some of the products that we were going to see later in the villages. Colleagues from Bamako University arranged a visit to a potter in Bamako who, interestingly enough, creates his pottery together with his wives and his old mother by using a potter’s wheel — this is not how is it done traditionally.

The next day, we departed for Kenieroba, 60 km north of the Guinean border, 70 km south of Bamako and one km west of the river Niger. This was the place we stayed in for almost three weeks as a team of several archaeologists and myself as an ethnographer and anthropological linguist. Kenieroba is a village that is traversed by a major thoroughfare with some small shops, mosques, school, infirmary and a mobile phone mast. The people of this area are mainly Mandinka, they speak Maninkakan (southern dialect) a Manding language related but not identical to the inofficial official language of Mali, Bamanakan.

Tradition and modernity go side by side in Kenieroba. Beside handicraft and retail trade most of the inhabitants are farmers with some livestock, Fulani herd the animals and market milk and meat. Around the village you will find small gardens where tomatoes, onions, vegetables and lettuce are grown for people’s own use and to sell by the roadside. Now, during the dry season, the landscape is characterized by generously distributed mango and shea trees on dry fields. During the rainy season people will start the cultivation of millet, rice, sorghum, fonio and maize. Close to Kenieroba, behind the millet and sorghum fields lie small settlements of Somono, Bozo and Sorko fishermen at the river Niger; people also drag up the riverbed looking for gold. Further north a ferry service is the only means of crossing of the river between Bamako and the Guinean border for cars and trucks ; the engine of the ferry has a defect , so it is pushed by a pirogue.

Film about ferry loading truck

My colleagues from archaeology are here to do excavations of several sites their surveyed. They will find lots of sherds of ancient pottery. However, I want to find out what the current ceramic production looks like. In am intrigued by how pottery is made and how production is conceptualized by potters. What are the names of the artifacts, what are the tools, what are the respective steps in the chaine opératoire?

The method that I will used is termed “visual anthropological linguistics.” I am doing semantic and anthropological field research. My goal is to research conceptualizations by recording words and their meanings in the Maninkakan language about artifacts and ideas about processes, beliefs that are created in any way to pottery. In addition I do a lot of interviews, e.g. about the distribution of goods and social networks of the potters. Thankfully, Christophe helps me as field assistant and translator and Marco helps me with filming on some days.

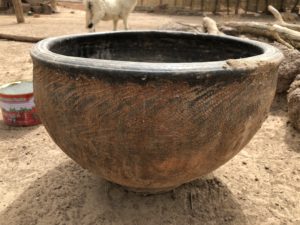

On the first day, we leave for Madina, a small village ten kilometers south of Kenieroba on the freshly tarred road to Guinea. It is a small village with several potter families. Madina traditionally had an endogamous group of potter-blacksmiths but the tradition has almost gone: at present only one blacksmith’s workshop is still active. The pottery produced here is mainly exported to markets along the river Niger up to Kangaba (20 km south) or as far as Bamako. However, most parts of the production are sold by the road or directly on the spot. At present, the potters have reduced their range of pots. The only pots that are still made are those for the production of traditional medicine in three sizes which are usually blackened directly after firing: furatòbi-dagà or dagà-nifin. Seemingly, other kinds of ceramics have been forced out of the market by imported plastics and aluminium. Especially with the dun (water pot) and wusulanbɛlɛ̀ (incense burner), individual and new variations are numerous. Further innovative products can be found in the fields of ovens, animal care and decoration. Old forms were completely abandoned for this for various reasons. Also in the way of production there are clear changes among the younger potters towards faster and less complex processes.

pots for storing water, on the one hand in the traditional form the fiɲɛn.

and with a longer neck based on the design of the productions of the region around Mopti and Segou the dun

Steamer ɲintin

large bowls for making karite butter fagà

small braziers or furnaces singò

and pots for burning incense in various shapes and sizes wusulanbɛlɛ̀

However, we do not get all this information until a few days later, because first the work in Madina is suspended: an inhabitant of the village has died and the village head informs us that we will have to stop until funeral services have ended. But he introduces us to the potter families and we can explain our plans.

The following day we decide to drive to the village of Kansamana, which is also a blacksmith and potter village but situated on the opposite side of the Niger. After an adventurous pirogue ride and driving over sandy tracks on motorbikes we finally arrive at the spot. That day happens to be market day in Dangassa, a place three kilometers away, so people are out and no-one is producing pots. So we go to Dangassa. All the potters are at the market offering their goods to the traders who come from Bamako and buy in bulk.

We get the opportunity to interview the old potters about the origin of their families, traditions of and changes in production, the mode of present and historical distribution and their social relations with other villages.

We learn that blacksmith workshops in Kansamana are commercially very active and that pottery production is also on a large scale in all households. Ceramic production is family and women’s business: all women of a household work together with their daughters and older grandchildren.

Even the little children help to prepare the clay.

Even a brief look at the artifacts reveals that the variations of some pottery are even more daring than in Madina, some of the pottery has very long necks, attached decoration, long handles. However, we get explained that traditions and style have changed: shape and decoration are adapted to the trends of the ceramics market and based on customer’s wishes in Bamako in particular.

In the next days we will be crossing the Niger regularly and we will be in Madina even more frequently. Christophe and I try to see as many details of the complete chaîne opératoire (ceramics production chain) as possible. Apart from interviews we document all details and steps on film. We will watch the videos together with female potters in order to ask for linguistic terms and in order to understand the cognitive conceptualization of of the production process.

Working like that we collect words, terms for things and gestures in Maninkakan. We also visit the clay pits, we film the processing of the clay, the construction of the different pots from the base to the rim, the decorations. We use the opportunity to talk about the loss of some traditions and are also present when the pots are fired.

In the evenings Christophe an I discuss the many details that come to mind when watching back the film sequences and especially the semantics of the vocabulary. In Kansamana we also take the opportunity to conduct an interview with a blacksmith, the male component of the blacksmith-potter caste .

.

On a trip to another small village another 10 km south of Madina, already in the Kangaba area, we further visit the workshop of the only remaining aged potter there. Her sister welcomes us but unfortunately the potter is travelling. I notice that the fiɲɛn. in the compound has a striking decoration but I can’t get further information, unfortunately nobody has continued the pottery business here.

.

After 15 very full days I feel I understand some more about the pottery of Madina and Kansamana. This is mainly due to the fact that all these women and also the men reacted with incredible patience and openness to our questions and we open to show us everything we wanted to see.